Locating an address in Lowry Hill, East Isles and most of Kenwood is a fairly easy task. The orderly arrangement of alphabetical and numbered streets is in keeping with Minneapolis's reputation of Scandinavian efficiency and has the simplicity of IKEA instructions.

Every city map should come with an Allen wrench. The streets are not all right angles as they must work with the contours of the lakes, but they are systematic, except for a few streets. So, where did 23rd Street go?

Street Nomenclature Issues

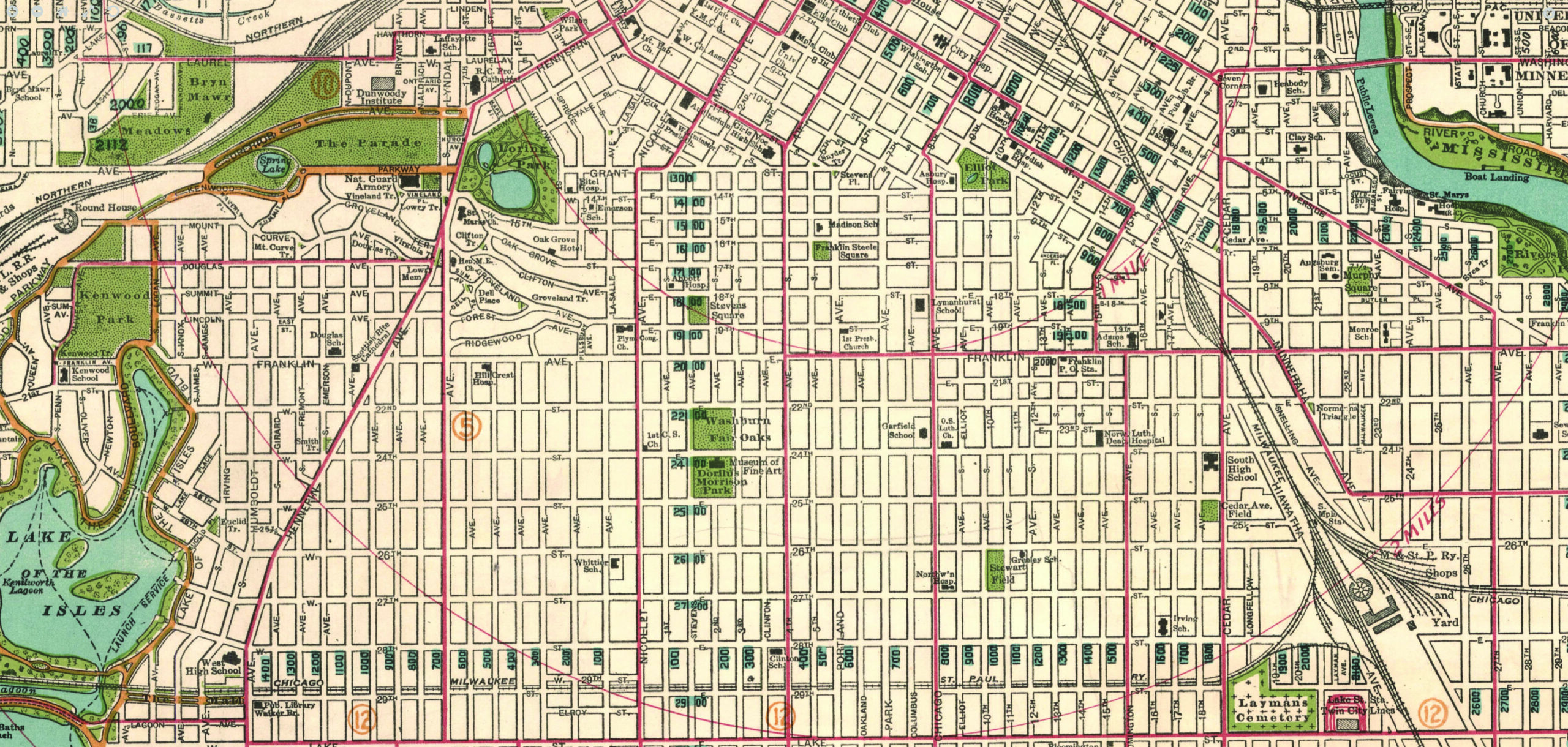

This orderly street system resulted after the initial chaos of the February 1872 merger of the cities of Minneapolis and Saint Anthony. George B. Wright's 1873 map of the enlarged Minneapolis shows several streets bearing the same name or number.

Even before the merger, the Board of Trade recognized the impending street name dilemma ma and requested on June 22, 1871, that committees be formed “to devise a numerical system of names for streets and avenues, so far as it is practicable to supersede the present arbitrary designations … while the city is young and extending.”

In June 1873, postal concerns arose regarding the free delivery system that would take effect on July 1, 1873. Postmaster George Keith stressed that “street nomenclature is also badly mixed in some parts of the city,” making it difficult for carriers to make timely mail delivery. Tangle town received its moniker for “its labyrinth of irregularities in names and streets.” The Minneapolis City Council convened to work on a solution.

The Ordinance of August 1873

On Saturday, August 16, 1873, the Minneapolis Tribune posted “An Ordinance — Changing the names and designations of the streets of the city of Minneapolis.”

The City Council had not just replaced the duplicate names; they had made a major overhaul of the city map. Two lengthy columns listed the numerous name changes. Over 200 streets had new names.

The City Council had chosen simplicity and order over variety. Linden, Pine, and Willow were axed; Christian saints were sacrificed. These street names were replaced by numbers and made the city streets orderly and humdrum.

Initial Public Opinion

With any civic policy, concern and questions arose as recorded in letters to the Tribune. After an article suggesting that the City Council had gone too far and that names should be reinstated, an August 26, 1873, reply stated, “Newcomers find [the street system] very easy, and all will more readily adapt themselves to the change by getting their house numbered at once, and having their let ters delivered."

One writer by the name of Pushit teased about having to buy a map in order to determine where he lived, and that police officers should be required to carry pocket compasses to assist. However, he voiced a real need.

He requested that "proper signs be placed at the corners of all the streets and avenues to enable people to know where they are." He stressed that money should be allocated, and signs should be ordered. They were not.

Franklin Avenue to Lake Street

The City Council's desire to have uniform numbering had a hiccup when it attempted to organize the platted area between Franklin and Lake Streets. In the 1872 map there are 12 blocks mapped between these two major streets 21st to 32nd. The Blaisdell Addition (1874) was revised in 1882, and both 21st Street and 23rd Street went missing.

It seems that the City Council wanted to have just ten blocks between the two major roads of Franklin (also called 20th Street at one point) and Lake (30th). The solution was to start with 22nd, skip 23rd and continue numerically from 24th. When Kenwood named its streets, it was able to use 21st. Otherwise, 21st and 23rd exist only between Chicago Avenue and Bloomington Avenue.

Too Many Numbers

As the growing city added land to the west, the adherence to numbers continued. An 1885 city map shows that west of Lyndale, the streets between Douglas and Franklin were all numbered avenues.

On November 23, 1873, the Tribune newspaper carried a follow-up street name article about the postal request for house numbers. When implementing the house numbers, it became necessary to again change street names because of the overuse and confusion with numbered streets and avenues.

The city engineer suggested that the streets west of and parallel to Lyndale Avenue "be named in alphabetical order." A curious list then appears: Afton, Baden, Clyde, Devon... None is a name that was ever used.

In the 1887 city atlas, the numbered avenues bear the alphabetical list we know today. It is unclear who chose the names and the process for doing so; however, there is certainly an emphasis on military figures, scientists and poets.

Any non-numbered street was amended as needed. Irving Avenue superseded Euclid Avenue (only to remain as a four-block Euclid Place). Arthur Street, the one-block street south of Franklin, was absorbed into James Avenue.

Missing Street Signs

Perhaps this confidence in the grid and alphabetizing and numbering gave the City Council a false sense that any person could find the way around the city.

However, people complained that one "found himself in a maze of streets, beautiful and orderly...but not a single street sign." The scarcity became a safety issue, as stressed in an August 1909 Tribune article. "The work of the Minneapolis police department is delayed and impeded by the lack of street signs."

This led to a realization that no one knew who was in charge of the street signs and that the street commissioners had ignored a growing problem. The Tribune continued to press the issue by printing articles about the great signage in Buffalo, San Francisco and Des Moines.

A street sign committee of the Publicity Club was formed. On November 25, 1910, every member of the City Council voted for street signs. One thousand lighted signs were ordered.

Modern Times

Perhaps our digital maps on our pocket computer phones have made all this work and this organized system less noteworthy. Perhaps we should return to the colorful names of Cataract and Salome Streets and let Mary Ann, Helen and Pearl have their namesake streets again.

Or, perhaps, we can sleep easily knowing that when the space aliens invade and shut down the World Wide Web, we in Minneapolis will still be able to get our mail.