Craig Wilson is the editor of the Hill & Lake Press and is Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian). He lives in Lowry Hill.

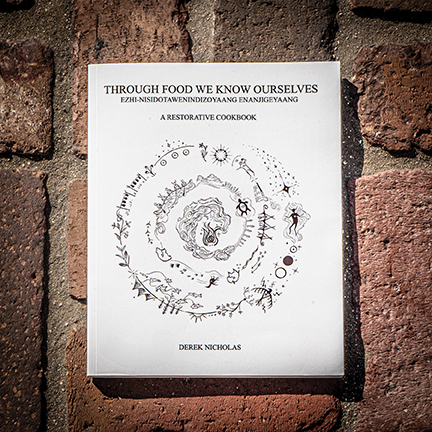

Derek Nicholas is a member of the Red Cliff Band of Ojibwe and lives in the East Bde Maka Ska neighborhood. He works across Minneapolis–St. Paul facilitating education around Indigenous foodways, highlighting the connections between food, culture and identity. His newly published cookbook, “Through Food We Know Ourselves,” is a restorative cultural journey rooted in Anishinaabeg traditions, legends and wild plant knowledge.

Can you share a bit about your background, your connection to the Red Cliff Band of Ojibwe and what brought you to the East Bde Maka Ska neighborhood?

I’m an enrolled member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, a tribal community in northern Wisconsin along the coast of Lake Superior. I carry that identity in all the work I do, especially around food, land and community. Growing up, food wasn’t just something we ate — it was something we lived. It told stories, held knowledge and brought us together. That understanding shaped my perspective and eventually led me to explore how food connects us to who we are and where we come from.

I was drawn to the East Bde Maka Ska neighborhood because of the energy around food sovereignty, culture and community healing. I wanted to be in a space where those conversations were not just happening but being lived out. Being here has allowed me to engage with other Native folks and allies who are passionate about reclaiming food systems, reconnecting with ancestral knowledge and building community resilience. It’s not just about food — it’s about identity, healing and remembering who we are.

You work deeply in Indigenous foodways here in the Twin Cities. What does that look like in your day-to-day life?

It depends on the day, but at the heart of it my work is about reconnecting Indigenous people with our traditional food system. One day I might be out foraging. The next, I’m in a classroom with students, teaching about the cultural stories behind our foods, how to cook with traditional ingredients, or why food sovereignty matters.

How do food traditions help connect people — both Native and non-Native — to culture, identity and place?

Food is one of the most powerful connectors we have. For Native people, food is tied to every part of who we are — our stories, our languages, our ceremonies and our relationship to the land. When we prepare or share Indigenous foods like manoomin (wild rice), we are not just eating — we’re engaging in a cultural practice that goes back generations, nourishing ourselves physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually.

Food has the same potential for non-Native people too. Everyone comes from somewhere, and every culture has food that tells a story about where they’re from and what they’ve been through. When people take the time to understand their own food traditions — or engage respectfully with Indigenous ones — they’re connecting to something deeper than just ingredients or recipes. They’re reconnecting to identity, values and place.

In the Twin Cities, I’ve seen food bring Native and non-Native folks together in beautiful ways. Whether it’s through community feasts, land-based workshops or foraging walks, these shared experiences open up space for healing, learning and relationship-building. Food can be a bridge if we let it. It reminds us that we all belong to the land, and we all have a responsibility to care for it — and each other.

What inspired you to write “Through Food We Know Ourselves,” and why do you call it a restorative cookbook?

The biggest inspiration came from what I see as one of the most pressing challenges in Native communities today: identity confusion, especially among youth. A lot of young Native people are struggling to figure out where they belong in this world. One major factor is our school systems, which often take a one-size-fits-all approach that doesn’t reflect our ways of knowing, our histories or our values. There’s a deep disconnect between what’s being taught and what many of our young people need — to feel seen, understood and empowered.

I wrote “Through Food We Know Ourselves” because I truly believe Indigenous food systems can help restore that sense of identity. Food touches everything — whether you’re a moccasin maker, a seed keeper or even a policy advisor working to protect water. It all ties back to Indigenous food systems, and that can reconnect us to who we are.

That’s why I call this a restorative cookbook. It’s not just about ingredients or recipes — it’s about restoring identity rooted in culture. It’s a reflection of the beauty, complexity and future of Indigenous food systems. I wanted to create something that shows what’s possible when we return to our food, our stories and our teachings.

Some recipes are based on legends and oral histories. Could you share one that especially resonates with you?

One that stands out is venison milkweed soup. Many of the ingredients in that recipe are wild foods I first learned about from a dear elder — someone who took the time to walk with me and teach me.

What has been the most rewarding part of creating this book, and how has your community responded?

The most rewarding part has been seeing how it resonates with the community. Hearing from people who say a dish reminded them of their grandmother, or that they’re excited to forage for an ingredient they hadn’t used before — that’s what makes it all worth it.

The response has been supportive and powerful. There’s been a sense of reclaiming — not just recipes, but relationships to land, food and one another.

How do you see Indigenous foodways shaping a more sustainable and connected Minneapolis–St. Paul, and how can neighbors support that work?

In the Twin Cities, we’re already seeing Indigenous food sovereignty take root — through community gardens, Native-led organizations reclaiming traditional knowledge, or chefs reintroducing wild ingredients in respectful and innovative ways. Neighbors can support this work by showing up — by attending Indigenous food events, supporting Native-owned businesses and advocating for equitable access to land and resources. Even small acts, like learning the names of local plants or where your food comes from, help build that connection.

What do you love most about living in the East Bde Maka Ska neighborhood?

What I love most is all the Native plant restoration work happening here. It’s especially noticeable along the Greenway bike trail — you can really see the land coming back to life. Watching those plants return season after season is exciting. It’s a quiet but powerful reminder of what was always here, and what can return when we care for the land in the right way. It feels good to live in a place where restoration isn’t just a concept but a practice.