Editor’s note: The Hill & Lake Press invited community voices from multiple faith traditions and therapeutic fields to speak to the emotional, spiritual and civic moment Minneapolis is living through. Their insights reflect both shared grief and shared resolve. The interviews occurred prior to the murder of Alex Pretti.

Paula Chesley is a regular contributor and lives in East Isles.

Since the death of Renée Good, I have needed time to grieve and to make sense of this profound loss for Minneapolis and for our country.

Good, a 37-year-old Minneapolis resident and mother of three, was fatally shot by a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent during a federal enforcement operation in south Minneapolis — a shooting that has sparked national debate, protests and legal conflict over federal immigration tactics.

To help people process what many describe as an ICE occupation of our city, I reached out to faith leaders, community leaders and therapists to ask how they are supporting people who feel afraid, overwhelmed or unsure what to do next.

Across these conversations, several themes emerged. Nearly everyone emphasized the need to ground ourselves before taking action, both for personal well-being and to avoid rash decisions. Some spoke of grounding through prayer.

Others mentioned creating beauty, using weighted blankets, reading poetry, physical movement, quiet reflection and getting enough sleep. Many urged peaceful community action. Almost all spoke of the need to de-escalate and stay connected.

“It’s like a layer cake, except it’s not sweet.”

— Julia Edelman, LMFT

Julia Edelman, a licensed marriage and family therapist and chair of the Safety Committee for the East Isles Neighborhood Association, said the emotional responses she sees vary widely.

“People’s responses have been all over the place,” she said, “but everyone is responding somehow. For people with trauma histories, and really for all of us, it’s like a layer cake, except it’s not sweet. Each added layer takes a toll on our individual and community psyches.”

Edelman said some clients feel guilty for not doing more or for feeling frozen while others take action. “It’s imperative to honor it all,” she said. “What we are called to do each day is different for everyone.”

She said a helpful framework is to imagine support in concentric rings. “Once we’re grounded, who can you support? A neighbor. A family member. A friend. Then you expand outward — coworkers, your neighborhood, and eventually the wider world, if you have the bandwidth.”

“Oppression rarely stops because people ask nicely.”

— Imam Makram El-Amin, Masjid An-Nur

Imam Makram El-Amin, who has led Masjid An-Nur in North Minneapolis for 30 years and serves on the Downtown Minneapolis Interfaith Senior Clergy, described a mix of emotions in his congregation.

“People feel a spectrum of emotions, including anger — and rightfully so,” he said. “We are diverse politically, but the consensus is that what happened was wrong.”

He emphasized the long history of faith communities standing against injustice. “Oppression rarely stops because people ask nicely,” he said. “Change requires pressure. I don’t agree with every tactic, but strong emotions create a range of responses.”

On messaging, he warned that repeated narratives, even false ones, can shape public memory. “That’s why faith leaders must be consistent. Narrative determines how history remembers a moment.”

“When things calm down, that’s when the needs appear.”

— Kate Fischer,

Executive Director, Walk-In Counseling Center

Kate Fischer, LICSW, directs the Walk-In Counseling Center on Chicago Avenue South, where people can access free, anonymous therapy without appointments.

“We’re not unfamiliar with community-level trauma,” Fischer said. “What we’re seeing now is complex and ongoing.”

The center has seen rising demand but also increased volunteer interest. She noted that an immediate surge did not follow Good’s death. “Some people are activated. Others freeze. I think there’s a lot of freezing now.”

Fischer used a childhood memory to describe trauma’s delayed impact. After a fire in her grandmother’s kitchen, she recalled, her grandmother put out the flames calmly. “But when it was all over, she cried,” Fischer said. “It feels like that’s what’s happening here. “ When things calm down, that’s when the needs appear.”

“Be a presence of peace to the person three feet in front of you.”

— Pastor Arden Haug, Lake of the Isles Lutheran Church

The Rev. Arden Haug of Lake of the Isles Lutheran Church described widespread confusion and anxiety among his congregation.

“People are struggling to understand how people they trust can see this moment so differently,” he said.

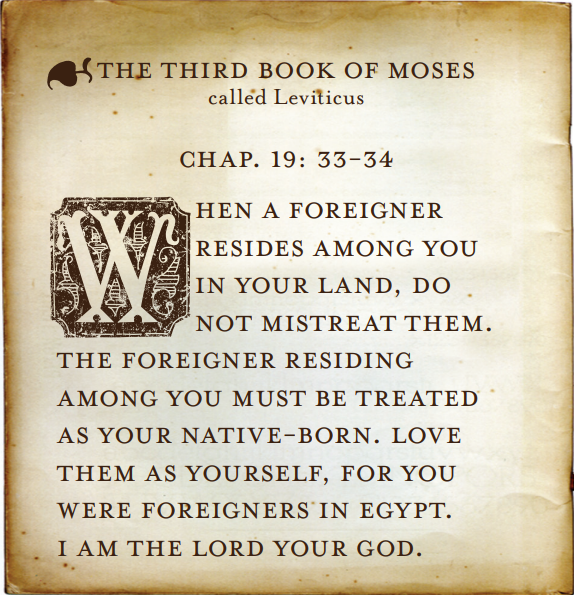

Haug noted that Lutherans have deep connections to refugee and immigrant histories. “After World War II, 20% of Lutherans worldwide were refugees,” he said. “This history shapes how we see immigration. The current policy does not make sense to us because innocent people are being caught up.”

His guidance was grounded and simple. “We can only be a presence of peace, compassion and listening to the person three feet in front of us,” he said. “You can’t do it for everyone.”

He added that following Christ requires a difficult discipline. “We must dare to pray for both Renee Good and Jonathan Ross. I know that stuns people, but that is what we must do.”

“I decided they were not going to steal my joy.”

— Robert Lilligren, Chair, Metropolitan Urban Indian Directors

Robert Lilligren, a Loring Heights resident and member of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe, described how, as after the murder of George Floyd, Native communities mobilized their Indigenous Protectors Movement and turned Pow Wow Grounds into a space for mutual aid.

He spoke of “blood memory,” a visceral connection to generations of state-sponsored violence. “You could see the trauma on people’s faces,” he said. “But also the desire to be in community.”

Lilligren said reactions differ between Native and white communities. “It matters that Renee Good was white,” he said. “White people may suddenly recognize, ‘That could be me.’ For Native people, it always feels like that.”

On sustaining hope, Lilligren grew emotional. “I decided early in this administration that I was not going to let them steal my joy,” he said.

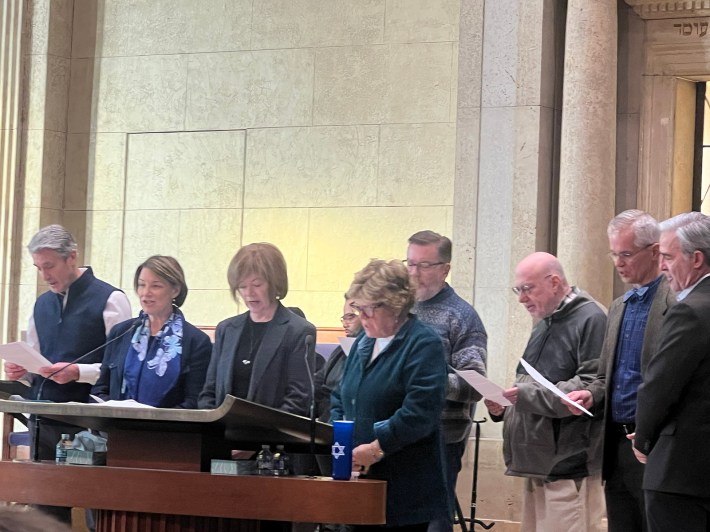

Rabbi Marcia Zimmerman of Temple Israel said her congregation feels fear, outrage and deep concern.

“The health of the city is our health.”

— Rabbi Marcia Zimmerman, Temple Israel

“We strongly believe in Jeremiah’s teaching that the health of the city is our health,” she said. “Our address is not just geographic. It is a mission.”

Zimmerman noted that most Jewish families in the United States are only a generation or two removed from immigration or persecution. “I’m the granddaughter of immigrants,” she said. “My parents-in-law were Holocaust survivors. This moment is frightening.”

She said the Downtown Minneapolis Interfaith Senior Clergy aims to elevate a narrative of hope. “We believe we are here to take care of each other,” she said. “When civil rights are attacked, that never ends well. What endures are the stories of people who stand on the right side of history.”

“…I reached out to faith leaders, community leaders and therapists to ask how they are supporting people who feel afraid, overwhelmed or unsure what to do next.”