For such a small, tranquil piece of property, Thomas Lowry Park has a convoluted, arcane history.

Sitting on fewer than 2.5 acres, the park is nestled between Mount Curve Avenue and Douglas Avenue at the end of Bryant Avenue. Once known as Hofflin’s Mound (1899), Douglas Triangle (1907) and Mount Curve Triangles (1925), the eponymous park now honors Thomas Lowry (1843-1909), a successful businessman who donated large tracts of land to Minneapolis for public parks like this one.

Thomas Lowry Park is one of several small parks owned by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board that serve as a neighborhood green space with a natural landscape design.

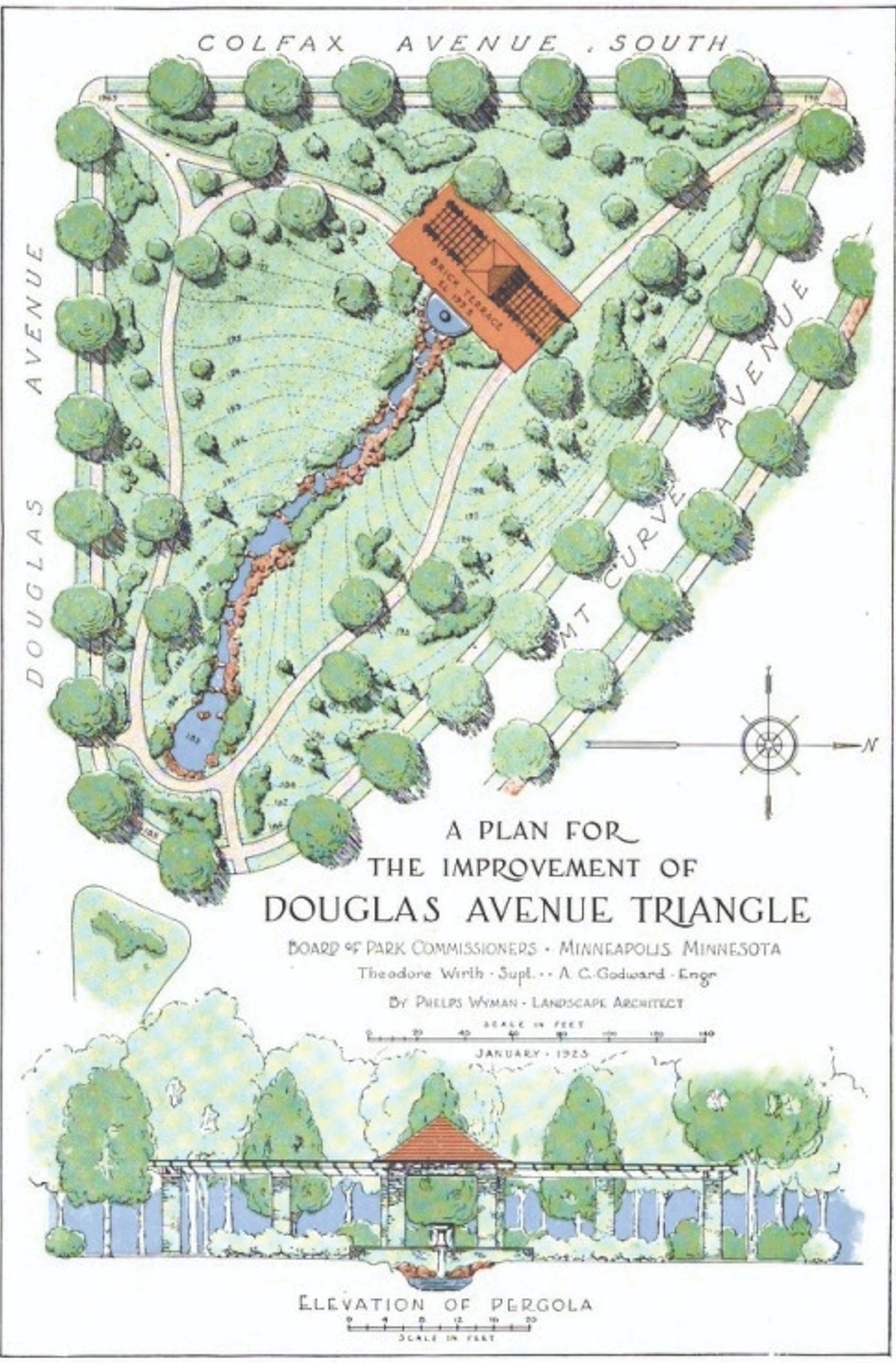

The pastoral design created by landscape architect and Park Board Commissioner Phelps Wyman (1870-1947) in 1922 may seem uncomplicated with its flowing water, meandering brick paths, assorted plants and flowers, and simple pergola, but it has required the dedication of several generations of neighbors over 100 years for Thomas Lowry Park to become this serene neighborhood haven.

Thomas Lowry Park is part of the Groveland Addition (1872),

one of the early additions to Minneapolis as the city expanded west. In 1874, Thomas and Beatrice Lowry elevated the neighborhood when they built their brick Second Empire-style mansion on a five-acre parcel at 2 Groveland Terrace (now the site of the Walker Art Center).

Thomas Lowry then decided to put the rest of the surrounding property that he owned on the market. The city’s new money left the congested downtown areas and began building elegant homes in this 75-block area between Lyndale and Fremont.

In the center of the desirable neighborhood was an oddly shaped piece of land, block 29, created by the serpentine border of Mount Curve Avenue as it connected to Douglas Avenue. A September 1, 1907, Minneapolis Tribune article offers some background on the early neighborhood development.

There was a steady stream of municipal improvements until there was “practically no unbuilt portion of this property except what was then known as Hofflin’s Mound.”

The article explains that in 1892 the area at Mount Curve and Douglas was 30 feet higher than today and that “this enormous bank was all removed except the block between Mount Curve, Douglas and Colfax owned by Joseph R. Hofflin,” described as an “unsightly gravel bank setting about the three streets.”

People came to the top of Hofflin’s Mound to get a view of the city. Hofflin owned and ran the only all-night drugstore in the city located at 101 Washington Ave. S. but tried a real estate career that ended in 1903 when the real estate company of Hofflin & Conrad was dissolved.

Hofflin sold the Lowry Hill land and its nine lots to a Mrs. Hooper who with Lowry’s help leveled the land. A 1903 map shows that the same parcel was re-drawn with only five lots.

The 1907 article also states that the neighborhood residents, including Thomas Lowry, were now interested in preserving the beauty and property values of Lowry Hill.

At a Lowry Hill Improvement association meeting, a Mr. Bright made a passionate speech to have the park board take over this piece of land and stressed that the possibility of flat buildings on this land would “practically kill the entrance to the most noble residence property that Minneapolis possessed.”

Real estate developer Edmund Walton said that such buildings would halve the property values of the neighborhood. A plan for a park with a monument to the Minnesota First Regiment was adopted. Thomas Lowry was part of the group who petitioned.

In April 1908, the Lowry Hill association formally offered to secure and “make fit” the small triangular section (.07 acres) on the eastern side.

This is the first example of the neighborhood attempting to spend money and personally care for this piece of land. It is likely that they were offering private money to fix at least the small triangular portion.

However, in September 1908, the park board denied the request for the simple reason that it did not own the land. There could have been push back from other neighbors who were already paying an assessment for the new Kenwood Park, acquired in 1907.

Consequently, the park board adopted a committee recommendation that “further consideration of this matter be indefinitely postponed.”

However, in 1911, the park board listed this small triangle as a 1907 acquisition and referred to it as the Douglas Triangle. How it was acquired or paid for is unclear. To the west of the Douglas Triangle stood the larger parcel that was still not developed.

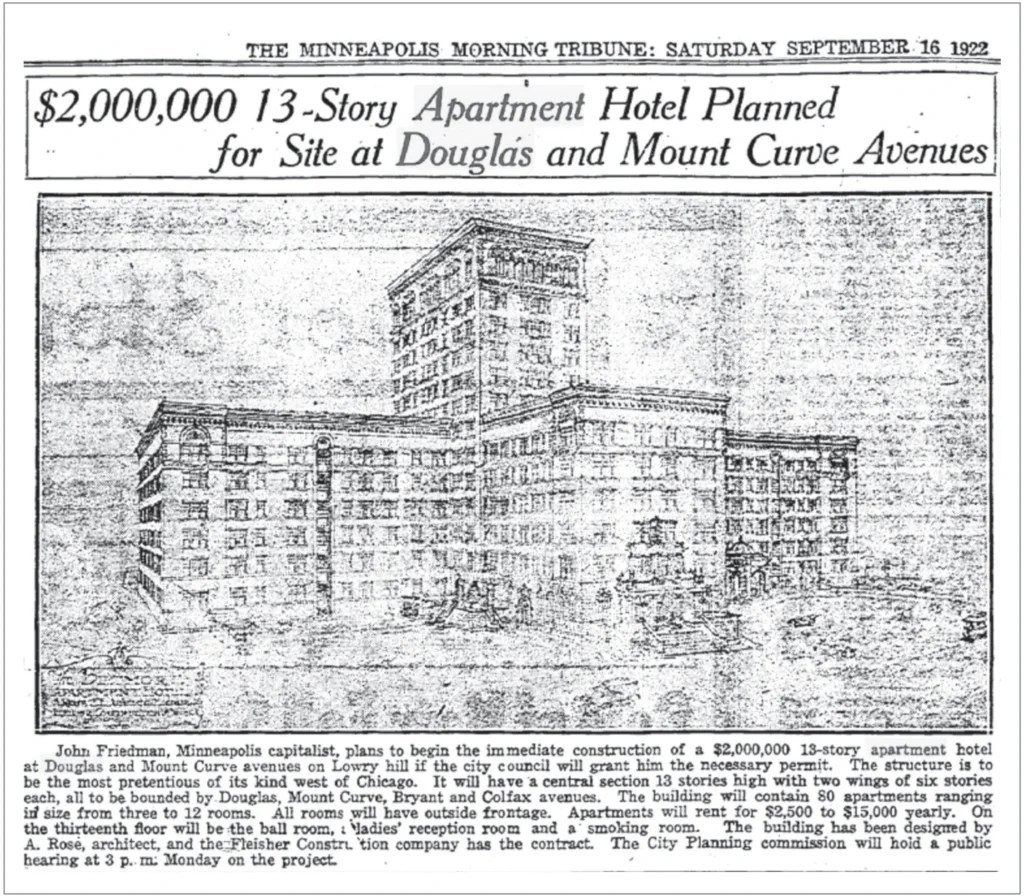

John Friedman, a Minneapolis capitalist, noticed it and saw a great location for a luxury hotel. On Saturday, September 16, 1922, the Minneapolis Morning Tribune had a headline – “$2,000,000 13-Story Apartment Hotel Planned for Site at Douglas and Mount Curve Avenues.”

Well, that certainly grabbed the attention of the neighborhood. The language under the image of the hotel didn't soften the blow — “The structure is to be the most pretentious of its kind west of Chicago.” The advertisement concluded with the announcement of a public hearing on Monday.

One can only imagine the discussions and organizing that ensued that fall weekend about early activism. Follow-up articles in the Morning Tribune indicate that the neighborhood banded together to block the hotel and create a park.

The Minneapolis park commission used eminent domain to acquire the property from Friedman, who made “no objections to the arguments of his neighbors and stated that if the park board wished to convert the land into a park it would be satisfactory with him.” The “benefitted properties” surrounding the new park were to be assessed over ten years to pay off the bonds.

As much as people wanted to stop the hotel, there was a lot of debate as to the assessment calculations. One can see from notes and drawings that the board went back and forth on who should pay. They questioned if assessment should have been all the way to Franklin or just to Lincoln.

T.B. Walker did not like that his large estate was assessed 3% of the total cost and felt that 1% was fair. It took a lot of haggling to reach the accepted payment plan in May 1923 and the rest of the year to get the bonds in place.

Theodore Wirth, the superintendent of Minneapolis park system appointed Phelps Wyman, a landscape architect, to create the design. Wirth wrote, “the little park will be very attractive and in a class of its own on account of its naturalistic effects in the heart of a residential district.”

If the neighbors were feeling buyer's remorse, the December 21, 1922, Morning Tribune article should have brought them pleasure. The article explained the vision to make this historically unsightly spot quite remarkable.

It described “a brick terrace 80 feet long and 40 feet wide to be located on the highest point of the tract” with “a vine-covered pergola.”

It continues with a lovely description of the stream of water that will flow over various sized rocks embedded in a concrete base with the side “lined with field stones and planted with shrubbery.”

It specifies the “brooklet will start from a grotto basin in front of the pergola where the water will enter the grounds from under rocks, to produce the effect of a natural spring.”

The article concludes with mentions of the meandering concrete path, the removal of 7,500 cubic yards of dirt, and a special lighting system.

Wyman’s engaging plan was published in color in January 1923, and the artificial cascade of water led to the informal name of Seven Pools. The pergola was completed in 1925.

Wirth called the park one of the “most expensive undertakings” in the history of the park board at a total cost of more than $100,000 for acquisition and improvement, roughly $44,000 per acre. Once again, the area took on a new name and was officially named Mount Curve Triangles in November 1925 as Bryant Avenue still divided the space into two triangles.

Reports for the following years indicate that there were repairs needed periodically, but that the park saw no big changes. In 1984, the park board again renamed the space. It officially became Thomas Lowry Park.

This unassuming parcel of land was now an established part of Lowry Hill, a place where people came to picnic, play and gather. Problems to come were appearing in the cracks of the fountains and walkways as well as the failing pump.

Whether the neighborhood could preserve this idyllic spot would be the next challenge for Thomas Lowry Park and its dedicated community.