In 2018, the City of Minneapolis adopted its long-range plan, the Minneapolis 2040 Plan.

The city dramatically reduced regulations on development, including eliminating protections for single family housing and allowing much taller and larger apartments throughout the city, in the hopes that developers would flock to build more housing.

In total, the city hoped these changes would increase population by at least 75% over the next 20 years.

If this kind of growth were to happen, it would substantially in- crease population density.

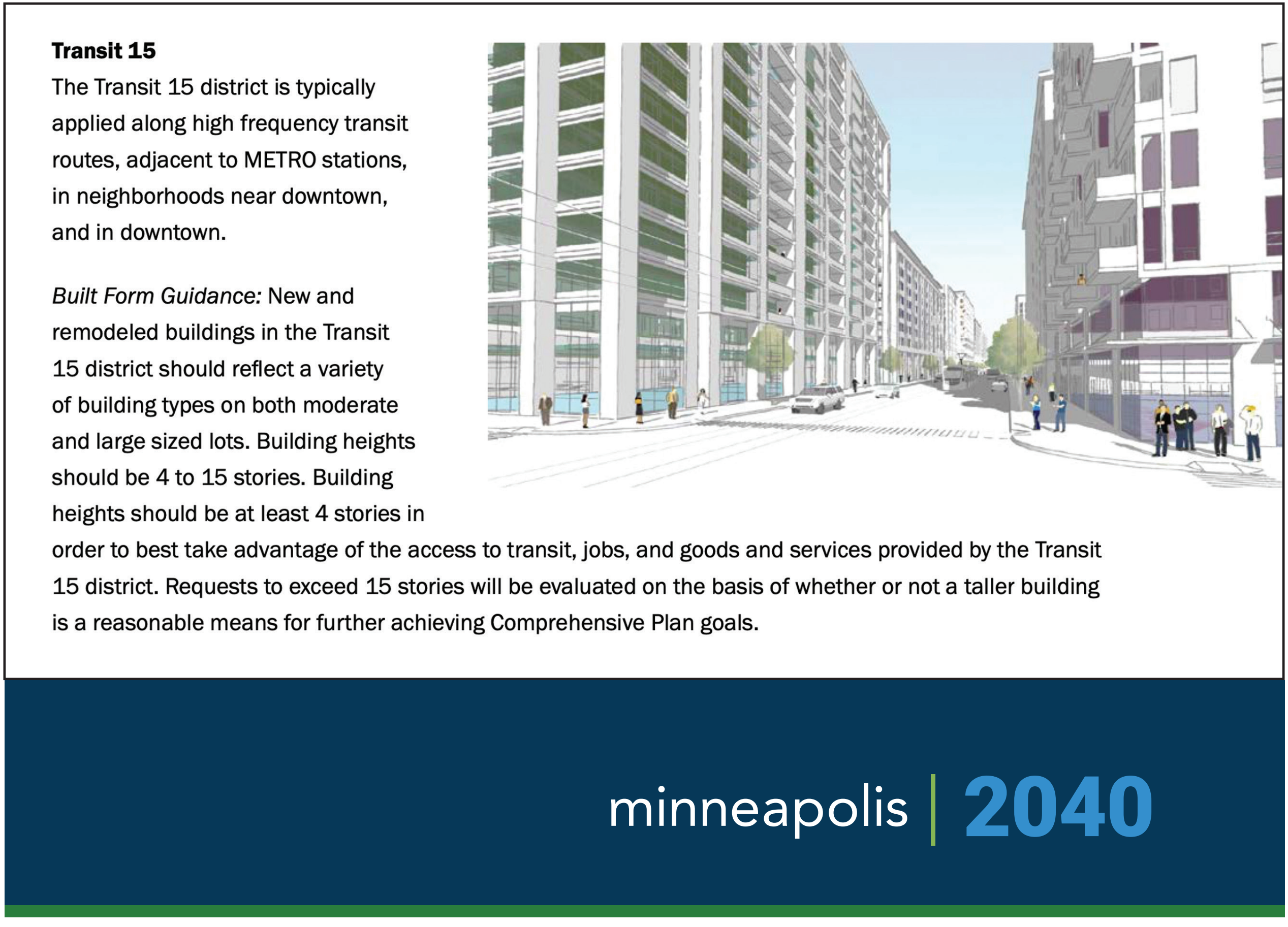

This picture shows what streets with high frequency transit bus routes and neighborhoods near downtown would become over the next 20 years.

This would include commercial corridors like Lake Street, Central Avenue, Nicollet Avenue and Franklin Avenue as well neighborhoods like Seward, Near North and St. Anthony East.

This kind of density, rivaling New York City, would also require different ways to get around.

Travel by automobile at densities like those in this picture would be impractical. There just would not be enough space for street parking and parking ramps. Instead, the city planned for a massive shift away from auto travel to walking, biking and transit.

Based on this plan, in 2020, the city adopted is Transportation Action Plan to implement these changes. The core of this plan was a 60% reduction in auto travel by 2030, with a presumption that 25% of trips would be taken by walking, bicycling would triple and transit ridership would double by 2030.

The city is now rebuilding its roads as if this is going to come true. How is it going?

Population Growth

According to the U.S. Census, the population of Minneapolis declined, from 430,710 in 2020 to 425,115 in 2023, about 1.2%. This is most likely because of the declining birth rate. It takes 2.1 babies per woman to have a stable population, and the U.S. is at 1.61. Homes are filled, just with fewer people.

Auto Travel

Vehicle miles traveled in Minneapolis declined 3% from 2016 to 2020.

From 2019 to 2023, miles traveled declined another 11%. This decline happened mostly 2019 to 2020 then rebounded from 2020 to 2021 and has remained stable since

This change is most likely due to a tripling of people working from home and a tripling of the number of minutes people spent at home alone as opposed to going out with others.

Transit

Transit ridership peaked in 2015, after the opening of both the Blue and Green light rail lines.

Uber debuted in Minnesota in 2015, and transit ridership declined 9% from 2015 to 2019 as a result. Transit ridership has fallen about another 40% from 2019 to mid-year 2024.

As a result, in Metro Tran- sit’s new 2027 transit plan, 8% of service will be an Uber-like ser- vice with vans instead of buses or trains.

Walking & Bicycling

Walking has declined precipitously. In the Twin Cities, walking declined 47% from 2019 to 2022.

Nationally, biking increased 37% from 2019 to 2021, then flat- lined in 2022.

The Twin Cities ranked 30th in per capita biking in 2019 and 33rd in 2022, actually increasing less than other metro areas, despite making heavy investments in bike amenities.

Impacts of Changes

Since the city started making roadway changes in 2018, deaths increased 79%.

There isn’t a measure of carbon emissions, but it is obvious to the naked eye that carbon emissions are up all over the city.

Roadway changes like on East Lake, Hennepin Avenue, Lake Street and many other places mean cars are now in congestion, idling where they were not just a couple years ago.

To put it mildly, it has been a climate disaster.

Minneapolis has doubled down on the desire to have cars idling unnecessarily recently by passing a resolution to remove I-94.

The Future Is Electric

There is a better future. It is electric vehicles. The UK Government, Department for Energy Security data shows that electric vehicles on average produce 47 grams of carbon dioxide-equivalents per passenger kilometer. Heavy diesel buses produce 97 grams on average and gas auto- mobiles produce 171.

If Minneapolis were serious about climate change, it would admit its “everyone should walk, bike and take transit” approach is failing and instead go all-in on electric vehicles.

This means ending its war on cars and reversing changes where it has increased carbon emissions and energy costs like Hennepin Avenue, Lake Street and others.

This means preserving and expanding parking because that preserves space for charging stations.

That means expanding, not eliminating, I-94 to reduce congestion and the energy cost of getting around the region, especially given that population growth is grinding to a halt.

I appreciate that this is a very different understanding of the solution to our climate challenge. But what we are doing now is failing badly. Instead of doubling down, we need to admit there is a better solution, one that everyone in the Twin Cities can adopt. And that is electric vehicles.

Will regional transportation planners change? Probably not. There is a huge activist industrial complex built around promoting biking and transit and none for promoting electric vehicles. Perhaps it is time for a new revolution. The future is electric.