Josie Owens is a regular contributor. She lives in Lowry Hill.

In 1975, Peter Williams (1952-2021) earned his BFA at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and embarked on an extensive art career as a social commentator, storyteller and professor. He is now being welcomed home to MCAD with the powerful and visually rich art exhibit “Peter Williams: Homegoing–A Call and Response.”

Keisha Williams, the director and curator of Galleries and Exhibitions at MCAD, has created a masterful show by focusing on three areas of Williams’ canon and surrounding his artwork with those of 15 fellow artists he once studied with, mentored or inspired.

Little has been overlooked in her tribute to this important artist. The blue walls complement the colorful artwork The didactics include the artists’ words along with relevant and historical context.

She has included a variety of artworks, including sculptures, paintings, photographs and videos. All focus on the complexities of the Black American experience. Keisha Williams wants you to feel the joy but also confront the message as “we honor legacy and celebrate life.”

Homegoing can mean welcoming someone back but also refers to the “funeral tradition in the U.S. Black community that celebrates a loved one’s release from this life and a reunion with God.” These “homegoings,” rooted when enslaved people were not allowed to gather in groups, include a call and response element.

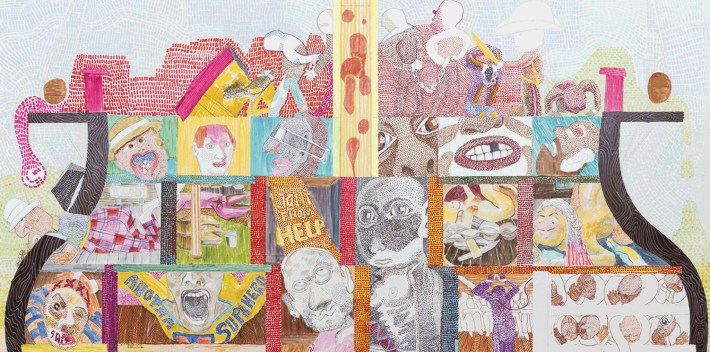

This exhibit explores that concept as these artists call and respond to each other about issues like incarceration, police brutality and racism as well as how to refute those and find peace. Keisha Williams has selected a Peter Williams work — vibrant, powerful, and often humorous — and surrounded it with other artworks that draw and build on that subject.

For example, in the section “Colorful Hard Truth,” Williams’ “Voyage Then and Now” (2019) has interconnected timelines of both a cruise and a slave ship and calls out with its images of violence and incarceration. Across from this painting, four other artists respond. Jovan Speller’s manipulated photographs of her family’s land ask how one can trace heritage when the mechanisms for doing so aren’t there.

Candice Davis’ artworks, dyed with her own blood, call out the throughline of generational trauma. In “Cotton Dreams” (2021), Sayge Carroll asks whether her father ever fully escaped the cotton fields when he finally became a “briefcase man.” Bobby Rogers responds positively in “Family Ties” (2022) by rebutting the myth of the absent Black father with a photograph of three Black males finding joy in the face of systems designed to tear the Black family apart.

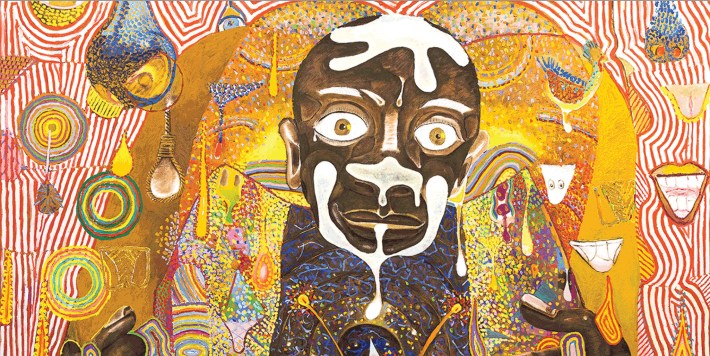

In the section “Speak Up, Document, and Leave a Record,” the exhibit focuses on the Black Lives Matter movement that was recorded on iPhones and exposed the world to racial profiling and police violence. Williams’s “[I Can’t Breathe Mother]” (2020) contains a shrouded photographer, eerily like a hangman, photographing the words “I can’t breathe Mother” in place of a Black body. At Derek Chauvin’s trial for the murder of George Floyd, Sean Garrison documented the emotion of the crowd outside who were braced to hear “not guilty.” He recorded a collective gasp of “love rising” at the guilty verdict with light swirls of blue in “Walking on Air” (2021).

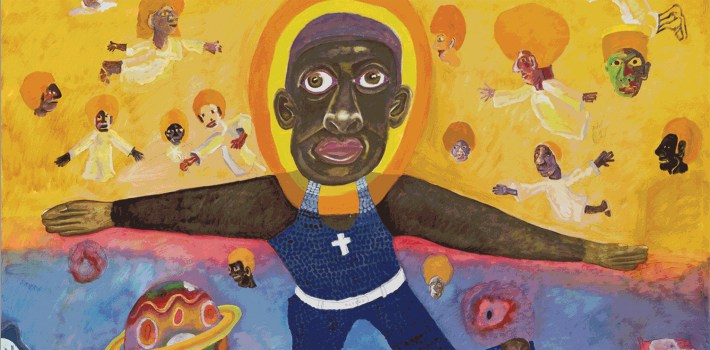

The final section, “Ascendance,” asks where Black people can go during time fraught with pain and sorrow. This section includes Williams’ “Jesus Died For Somebodies Sins, But Not Mine” (2020), a portrait of George Floyd ascending to heaven, as well as his Afrofuturistic work in which Black astronauts escape Earth and end the cycles of oppression. Leslie Barlow’s “Heavenly” (2025) offers escape in the Black cosplay community. Lamar Petersen invites respite in floral gardens. Leeya Rose Jackson’s “Universal Change” (2023) is a large colorful graphic artwork that inspires with an Octavia Butler quotation from her dystopian novel “The Parable of the Sower.”

When asked about the impact of his artwork, Peter Williams said, “[Viewers] are seeing their relationship either as a Black person, or to Black people, or their relationship to death or meaningfulness or authority in some kind of balance or counterbalance, counterweight to the way the world is operating right now.” Keisha Williams also hopes that by interacting with these layered pieces, the viewer will understand that Black Americans “have experienced this and look at all this beauty.”