What we now recognize as Lake of the Isles — with its distinctive twin islands, curving shape, and connecting canals — once looked entirely different.

Known as Wíta Tópa (“Four Islands”) by the Dakota people, the area was a shallow lake and marshland with none of today’s picturesque features.

From the late 19th to the early 20th century, this natural wetland — shaped by centuries of ecological succession — was radically transformed by landscape architects as part of the City Beautiful movement.

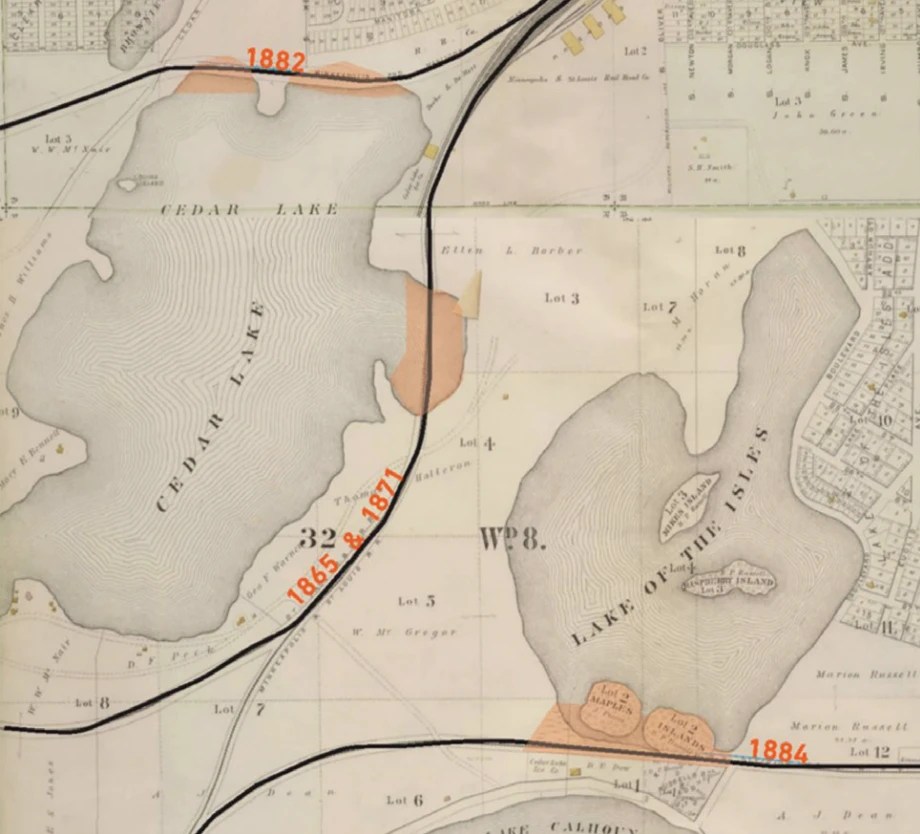

The first major alteration came with the decision to increase the amount of land between the marsh and nearby Bde Maka Ska to accommodate a railroad. This involved filling in the south end of the lake, merging two of its original islands with the shore.

Led by Horace Cleveland, the first phase of development replaced native marsh and forest vegetation with groomed lawns and ornamental plantings. Open water replaced wetland, and over time walking, carriage and driving paths were laid out along the newly defined shoreline.

In 1911, Theodore Wirth — often called the dean of the American parks movement and namesake of Wirth Park — oversaw a second major intervention. This phase involved dredging more than half a million cubic yards of fill from the lake, carving out canals to connect Isles with Cedar Lake to the west and Bde Maka Ska to the south. Fill was also used to enlarge the southern of the two remaining islands.

The redesigned shoreline was lined with woody plants, while the islands were reforested with trees and shrubs to give the illusion of a natural landscape. Over time, the islands were designated as protected wildlife refuges and left largely undisturbed. This allowed ecological succession — nature’s original sculptor — to resume its quiet work.

For the past century, these semi-manufactured islands have evolved into diverse, densely vegetated woodlands. The trees first planted have matured, but the canopy has not yet grown thick enough to prevent the rise of understory growth.

As a result, the islands are now filled with short juvenile trees and shrubs, and relatively few grasses or forbs — hallmarks of a forest in the later stages of succession.

The current stable deciduous forest is a testament to the resilience of the landscape and the power of succession to recover even from extreme human disturbance.

In contrast, the lakeshore continues to reflect the hand of the landscape architect. Along the paths, sparsely planted juvenile trees and short-lived nonnative species like weeping willows still dominate. However, pockets of natural regrowth have emerged — especially near the bridges and in the median between the walking and biking paths on the lake’s south end.

A century ago, these spaces were mowed and maintained. Today, they’ve been largely left alone, allowing succession to again shape the land. The result is striking: side by side, you can now observe the difference a hundred years of natural growth can make.

So the next time you admire the refined beauty of Lake of the Isles — the elegant bridges, the curving shoreline, the graceful plantings — take a moment to appreciate the equally remarkable work of nature. Succession has quietly reclaimed parts of this landscape, and the result is every bit as sculpted and sublime.