In 2017, the City of Minneapolis adopted a goal of zero transportation-related deaths by 2027. This was done in concert with programs like the “Complete Streets Program,” which explicitly prioritizes the safety of individuals who walk and bike over individuals who travel in cars, and the Minneapolis 2040 Plan, which envisions a 40% reduction in auto travel by 2040.

The city created a program called “Vision Zero” to implement physical changes to streets to achieve its goal of zero transportation deaths. These changes include reducing the speed limit from 25 mph to 20 mph, converting streets from four lanes to three, creating sidewalk bump-outs, narrowing streets to slow traffic, putting trees and plantings into the middle of streets, putting in bike lanes where there is no demand to reduce the width of the roadway, adding concrete barriers to separate bike and auto lanes and a myriad of other changes. In theory, this sounds like a good idea; in practice, more people are getting seriously injured.

Have these changes made the city a safer place to travel? No.

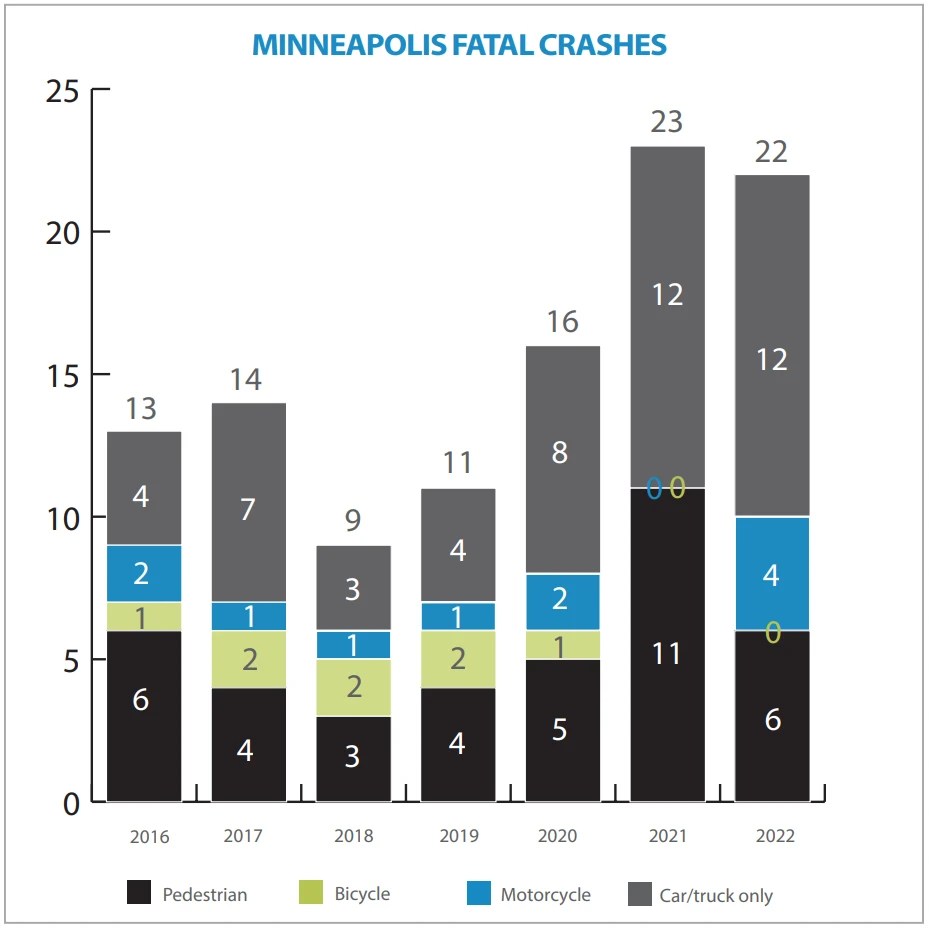

You can see how fatalities jumped after the implementation of the Vision Zero program in the graphic Minneapolis Fatal Crashes (City of Minneapolis). Total fatalities in 2022 were 87% higher than the average annual number of fatalities for 2016-2019, prior to the implementation of the Vision Zero program. To put this in perspective, in 2021, transportation-related deaths were the highest they have been in 24 years.

There has also been a shift in who is getting harmed.

The number of fatalities for persons traveling in automobiles and motorcycles has more than doubled over the last three years at an average of 11 deaths when compared to the average from 2016-2019, of 4.5 deaths. In fact, almost all of the growth in fatalities has been from people traveling in cars and on motorcycles (Minneapolis Vision Zero 2023 Annual Report).

All severe injuries, crashes that do not result in death but in serious bodily harm, increased 20% in 2021 and 2022, at 16 injuries, when compared to the average for 2016-2019, which was five injuries. Severe crashes also show this shift from pedestrians to drivers. Severe pedestrian and bike injuries declined 31% in 2022 compared to 2016-2019, while injuries to persons traveling in automobiles increased over 50% (Minneapolis Vision Zero 2023 Annual Report). For example, in 2022, there were a total of 28 accidents at 26th and Lyndale. Of the 28 accidents, 23 accidents occurred between July and December, after the City narrowed the street in July 2022 (Fox 9 News).

Many of the physical improvements for pedestrians have made driving less safe.

When streets are narrowed, it is harder for drivers to see pedestrians and other vehicles. When things are put into the roadway, like plantings, trees, and concrete barriers, it can be hard for drivers to navigate obstacles, especially at night when well over 50% of accidents happen despite substantially fewer travelers. For example, in 2022, the City of Minneapolis narrowed 26th St. and Lyndale Ave. S. There were 28 accidents at in 2022, and 23 after the city changed the street design (City of Minneapolis). One of these accidents left a woman severely disabled, even though she was simply exiting a vehicle at night on the substantially narrowed street.

This shift from injuries to pedestrians to injuries to persons traveling in cars is by design.

The Complete Streets policy explicitly prioritizes pedestrian and bicyclist safety over the safety of persons traveling in cars. The policy states: “Safety of the most vulnerable street users — those walking, rolling, and biking — must be the highest priority, because they are the most at risk” (Minneapolis Complete Streets Program).

The head of Hennepin County Transportation Planning explained to me that the kind of changes the City of Minneapolis is making to its roadways naturally increase the number of accidents. The hope is that the city is trading fewer severe injuries to pedestrians for fewer severe injuries to persons in cars. Unfortunately, this is not the case in Minneapolis where more drivers are injured than pedestrians.

What can be done?

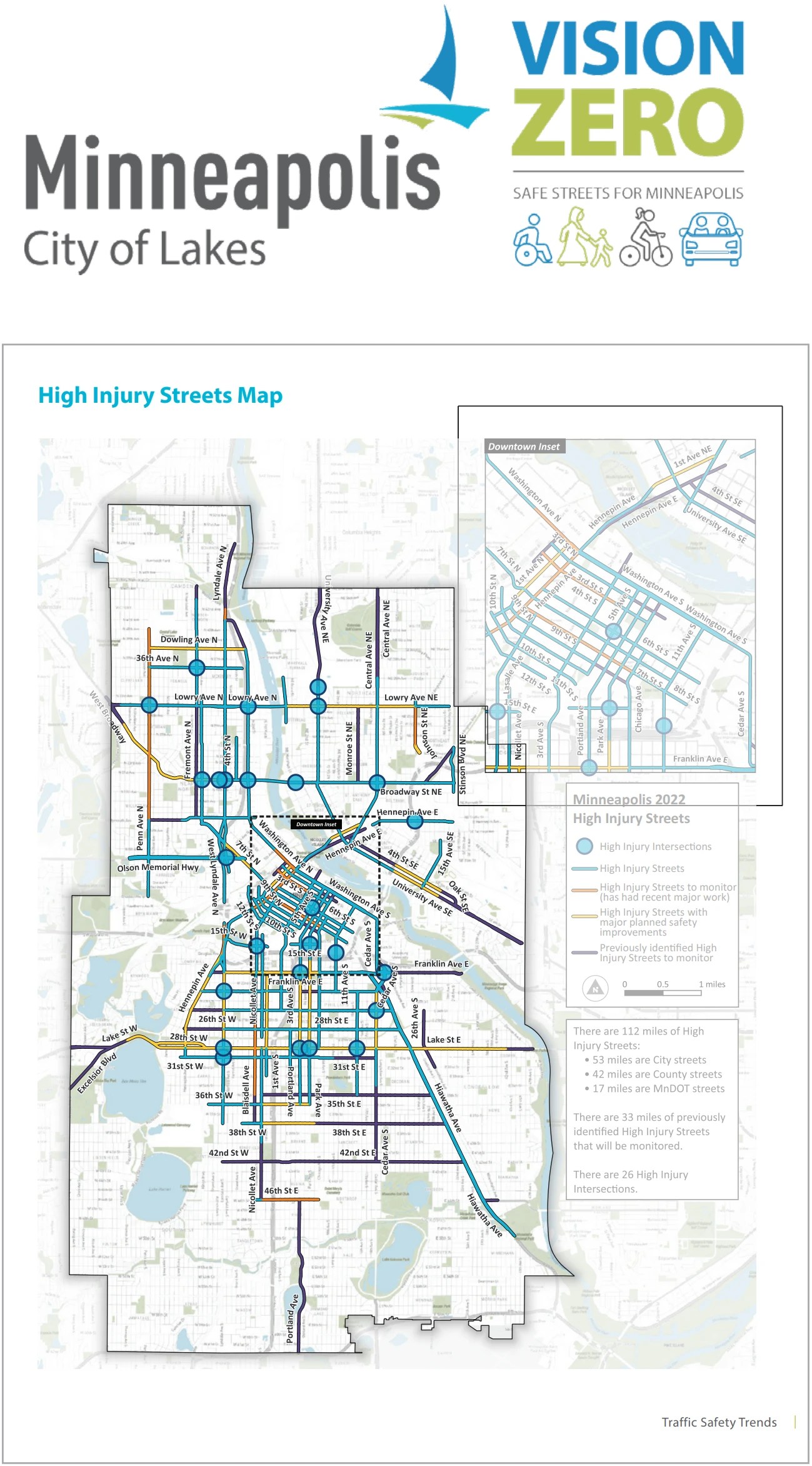

Infrastructure that reduces harm to pedestrians but increases harm to persons traveling by car should be used judiciously and only in places with high rates of pedestrian injuries. This map shows that the vast majority of pedestrian injuries and deaths are occurring on a very small number of streets (2022 Vision Zero Crash Study). Viewed in this light, the changes to Bryant Ave. S. or an unneeded bikeway at W. 40th St and W. 58th St./Sunrise Dr. make no sense. The city should focus changes on high-injury streets and leave other streets alone.

The city owes it citizens a pre-and post-implementation report for every roadway change.

For W. 26th St. and Lyndale Ave. S., the city should have to disclose that there were five accidents before its roadway changes and 23 afterwards. It should then justify why this is a good thing or remove the elements that are causing increased harm. In fact, the city owes its citizens a full analysis of the impact of the Vision Zero changes so far.

Engineers are licensed in the State of Minnesota to ensure that the things they build are safe and meet state and federal laws. Yet in Minneapolis engineers are building things that are increasing harm and injury, not reducing it. In the case of Bryant Ave. S., it also built things that violate state laws. Citizens can file with the Minnesota Board of Architecture, Engineering, Land Surveying, Landscape Architecture, Geoscience and Interior Design to request that the licenses of engineers building unsafe things be reviewed.

Last, it is abhorrent that the city is trading the lives of one group for another. Policies that prioritize harm of one group over another must be replaced by policies that focus on reducing injuries and deaths overall. Every life matters, and current city policy does not reflect this.