Ah, spring is here! The reason I know is that the tulips are up, and the throngs of people have returned to Lake of the Isles. We are so fortunate to have this environmental paradise in our backyard. As you walk, run, or bike, might I also point out an historical site to enjoy? The Peavey Fountain. The Peavey Fountain sits on a small triangular piece of land where Kenwood Parkway and Lake of the Isles Parkway meet. This small piece of land encapsulates so much of Minneapolis’s rich history – the rags to riches story, the milling boom and consolidation, and the bravery of Minnesotans in WWI.

Frank H. Peavey left his home in Maine in 1865 at the age of 15. Having lost his father at age nine, he was keen to make money and take care of his family. After a few jobs in Chicago, he secured a job offer in Sioux City, Iowa. In 1871, after some success and setbacks, he was able to move his family out from Maine and found the Peavey Brothers Company which sold farm implements. He also married Mary Dibble Wright, the daughter of Senator George G. Wright, after placing a newspaper advertisement “Eligible bachelor personal income $12,500 and $15,000 per year, age 21.” However, Peavey had a real business problem – the farmers were unable to make payments for the machinery they purchased from him because they couldn’t get their grain to market. Peavey found a solution by acquiring and building grain elevators all along the Dakota Southern Railroad to Minneapolis. He then accepted payments from the farmers in grain and guaranteed contracts with millers in Minneapolis. The year was 1874, and Frank Peavey was 24 years old.

In 1884, Frank and James Peavey moved their thriving business and families to Minneapolis. The business continued to grow and acquire other copycat grain storage facilities. In 1889, Peavey found a way around the high insurance premiums required for wooden grain storage. He enlisted the help of Charles Haglin, a Minneapolis contractor who built Minneapolis City Hall and the Grain Exchange Building, to build the first concrete grain elevator. While mockingly called Peavey’s Foley, the concrete grain elevator is still standing near the interchange of Highways 7 and 100 in St. Louis Park. Peavey’s success never stopped his desire for innovating. He earned his title of “Elevator King of the World” with more elevators including one in Duluth that had a capacity of 4,750,00 bushels. He acquired railroads and steamships. When he died from pneumonia in 1901, his heirs collected on a 1-milliondollar life insurance policy to incorporate the Peavey business which eventually merged with Conagra in 1982.

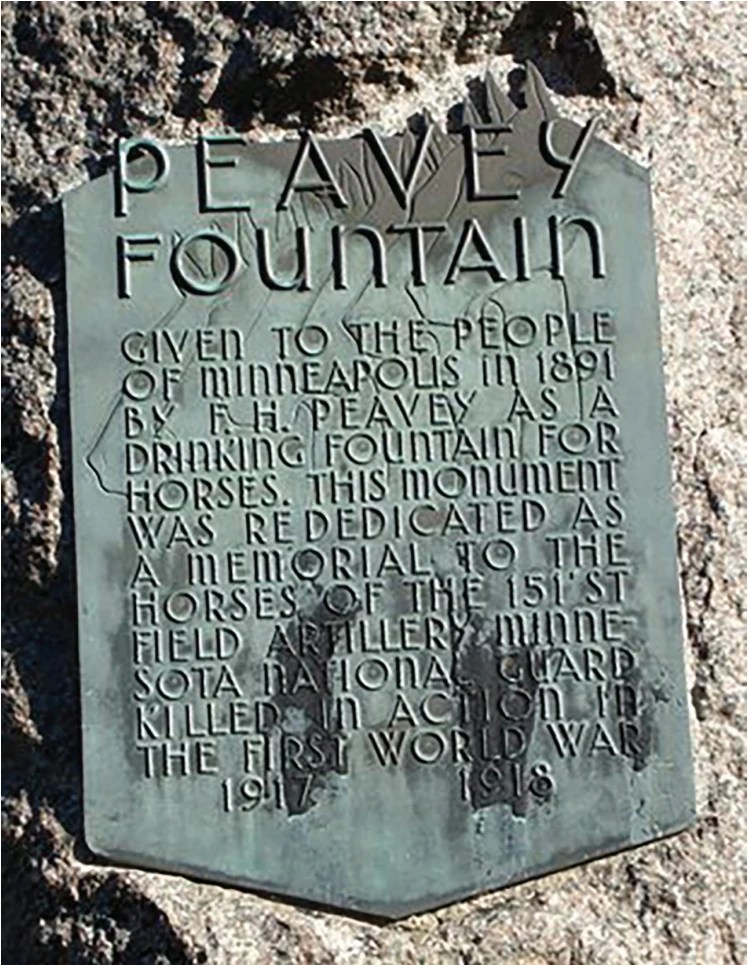

Working horses were the backbone of the growing Minneapolis and drinking fountains and troughs for the animals were spread throughout the city. Frank Peavey, who had depended on horses for transportation for his grain business, dedicated the Peavey Fountain in 1891. It was a place for these workhorses to stop and hydrate.

In the early 1900s, the automobile and electric powered transportation gradually replaced horsepower. However, the world was not ready to abandon this source of power in World War I. In fact, horses and mules were crucial for the transportation of heavy artillery and supplies to the front lines and ultimately to military success. It is thought that Germany’s loss was related to its shortage of horses toward the end of the war. In the years leading up to WWI, many countries created programs for acquiring horses. For example, at the beginning of the war, the British army had 25,000 horses and acquired 115,000 more under the Horse Mobilization Scheme.

When the United States entered the war, the Minnesota 151st Field Artillery shipped out to France, where it engaged in six campaigns: Lorraine 1918, Champagne 1918, Champagne-Marne, Aisne-Marne, St. Mihiel, and the climactic Meuse-Argonne. An armistice was signed November 11, 1918, ending the war. The 151st, nicknamed the “Gopher Gunners,” was the only Minnesota National Guard unit to see combat and their heroism was celebrated upon returning to Minnesota in May 1919. However, there were also the equine heroes. Eight million (8) horses, donkeys, and mules died in World War I. Unfortunately, at the end of the war, the majority of the animals provided by the United States were not transported home and were left in France. Of these, 209,033 horses died there.

Minneapolis did not forget the sacrifice of these animals. On June 22, 1953, the members of the 151st rededicated the Peavey Fountain to the horses in their unit who lost their lives in the Great War. A new plaque was placed at the site that read, “GIVEN TO THE PEOPLE OF MINNEAPOLIS IN 1891 BY F.H. PEAVEY AS A DRINKING FOUNTAIN FOR HORSES. THIS MONUMENT WAS REDEDICATED AS A MEMORIAL TO THE HORSES OF THE 151ST FIELD ARTILLERY MINNESOTA NATIONAL GUARD KILLED IN ACTION IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR.”

So, take a moment to visit this beautiful shrine to the often forgotten backbone of Minneapolis and the unsung heroes of World War I.